Words by Marc Haefele, Senior Arts Writer, Bermudez Projects

Wave your hand at a bright object like a small desklamp and out pours a generous stream into the greenish crystal sink of the master bathroom of the Sheats-Lautner-Goldstein house. If you remove the long glass prism that serves as the plug, the water drains into a slot in the floor.

That’s just one of the fine details that make this dwelling atypical of mid-20th century LA residential architecture and more like something “not of this earth.” This is the singular vision of late LA architect John Lautner, who was involved with this project over two decades. Like his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright, Lautner loved shapes and structures new to the eye.

There are hints of old SF covers in Lautner’s saucerish Elrod house in Palm Springs and the famed Chemosphere in the Hollywood Hills. But the Sheats-Lautner-Goldstein, Lautner’s masterpiece, moves beyond such imaginings.

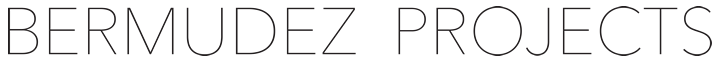

Now, LACMA will designate this 4,600 square foot structure, sitting on four tropical Beverly hillside acres, as a typical example of mid 20th century LA high-end housing. With its asymmetrical geometries of metal, concrete and glass, its cramped, hidden stairs like afterthoughts, its concrete and alloy furniture, its sudden edges, it’s actually like nothing else in the realm of human habitation. It is also kinda scary.

“You don’t want to wander around in the middle of the night,

looking for a glass of water,” said Roberta Leighton, James Goldstein’s assistant, allowing there was a spirit of danger to the place. Along with playfulness. Arriving, I cross a moat filled with big, elderly koi and turtles. The household staffers are setting out exotic flowers flown in from Maui.

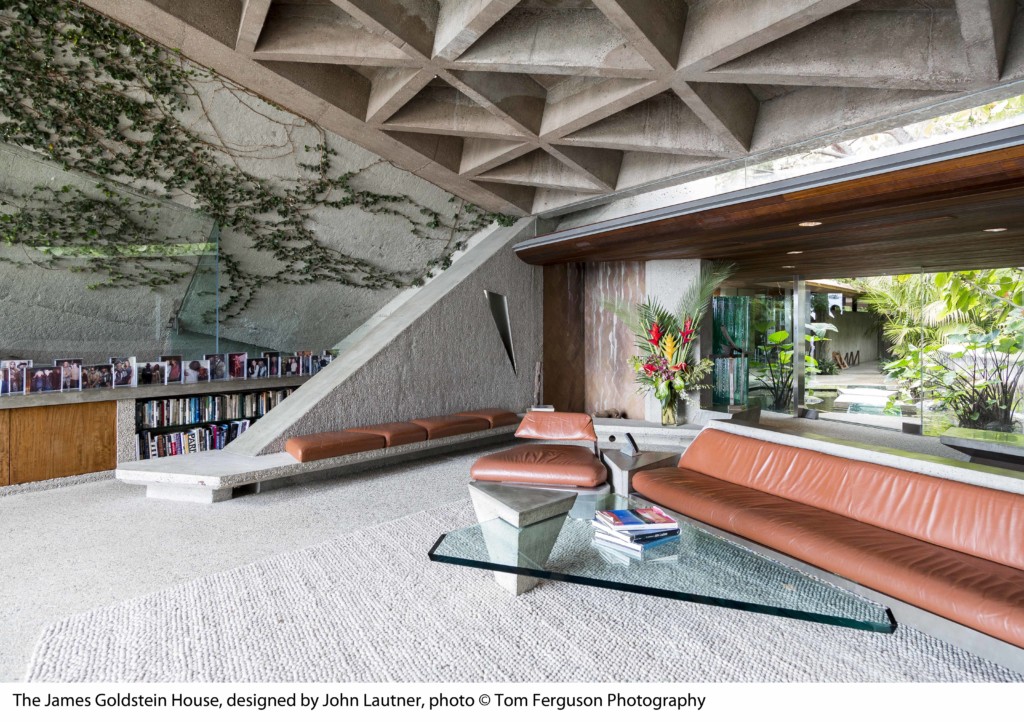

You have seen this place. It’s been in hundreds of commercials, fashion shoots, TV dramas, social gatherings and the Coen brothers’ 1990s cult film, “The Big Lebowsky.” Yes, that living room, with its views of all west Los Angeles, is where The Dude succumbs to a drugged White Russian prepared by Jackie Treehorn. In pictures, its coffered concrete ceiling resembles a giant waffle iron. But in reality, it’s the most natural possible opening of the house’s interior into the outdoors. Lautner wanted simple landscaping, but Goldstein preferred equatorial jungle. Now guests can pick their own bananas. It’s the California environment someone from Wisconsin—like James Goldstein—might have imagined as a boy.

Goldstein, an investor, bought the house in 1972, ostensibly to give more space to his favorite Afghan hound. The extent of Goldstein’s wealth is not obvious. He could, however, afford to employ John Lautner during his last years to reshape the 1963 house into something that incorporates Goldstein’s heroic vision as much as Lautner’s. The LACMA bequest is valued at $40 million, including $17 million for maintenance. Work on the property continues. The project eradicated a sibling Lautner house next door (Leighton says Goldstein had Lautner’s permission) to build an addition designed by Duncan Nicholson: a heliport-size tennis court over a private night club (Rhianna and Mick Jagger have been there), offices and, eventually, more.

I didn’t get to meet Goldstein. But his oversize business card indicates his major interests: fashion, architecture and basketball. His home’s stacked with books about all three, and wall photos show Goldstein with stars of couture and the sport. But he’s not forthcoming about himself.

In a 2014 interview, he said: “If people think I’m mysterious, who am I to discourage it?” The Stanford alumnus won’t give his age, but the university says James Goldstein graduated with a bachelor’s in economics in 1962. He wears high-concept cowboy outfits. In his dressing room shelf are more than 50 different Stetson-style hats and powered racks hung with hundreds of blingy car-coats. All this goes to LACMA, along with art by Ed Ruscha and De Wain Valentine plus a portrait by Kenny Scharf, along with outdoor works by James Turrell; Bernar Venet, Laddie John Dill and Zavier Veilhan.

According to Leighton, Goldstein spends seven months a year travelling. As long as he lives, he will have his singular home to return to. Once he is gone, LACMA will decide how best to present their first house museum. It will be as much a monument to its singular owner as its storied creator.