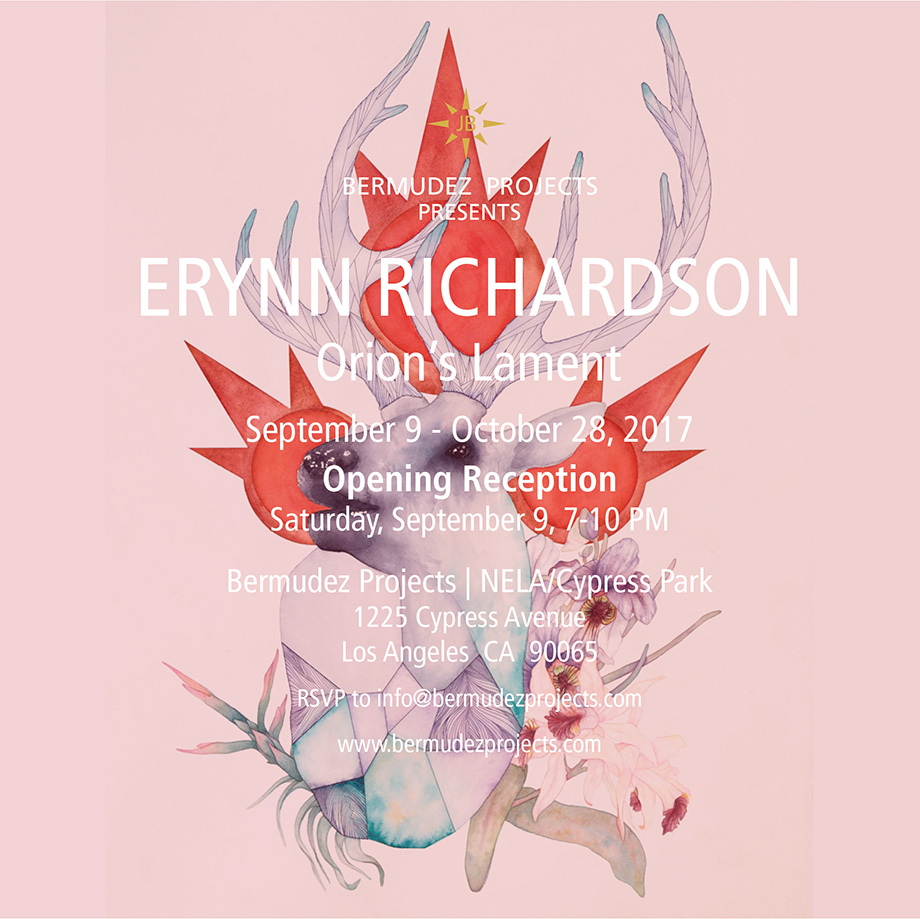

September 9 through October 28, 2017

Opening Reception: Saturday, September 9, 7-10PM

Before he became a constellation, the mythical Orion was a giant hunter with a big club and a propensity for forcing himself on chaste goddesses like Artemis. A Bronze Age Hemmingway, he came to a bad end after he vowed to kill every animal on Earth. Then Gaia – Mother Earth herself – summoned a huge scorpion to kill Orion to protect her progeny.

Now, via her new show, Orion’s Lament, on view at Bermudez Projects | NELA/Cypress Park, artist Erynn Richardson imagines the mythic hunter looking down from the sky at the present-day Earth, with its own modern hunters still in mortal pursuit of the living creatures of our tired, over-warmed planet. In her exhibit, she gives us, eloquently and passionately, the animals’ side of the argument about the practice of hunting, about the predator, and what we call “the game,” meaning the animal victim.

“I began to research big game trophy hunting practices, focusing on North America,” says Richardson. “‘The Super Ten’ of North American big game is a hunting title given to hunters who `take’ (kill) one animal from each of a set of ten categories. I wanted to mimic this title by painting 10 portraits of these animals, creating my own ‘Super Ten.’”

Orion’s Lament presents 10 ink and watercolor paintings on paper, representing one animal from each category of the “Super Ten,” as well as a series of large-scale paintings and studies. A full-color catalogue, along with a limited edition colophon “clamshell” set featuring prints of all 10 of Richardson’s “Super Ten” animals, will also be available.

The original 10 species categories are bear, big cats; deer; elk; caribou; moose; bison; wild sheep, wild goat and walrus. As the Super Ten’s founder put it: “to take one trophy from each of these ten categories would be a lifetime goal and an amazing achievement.” An achievement which, one imagines, will also shrink the population of the world’s array of wildlife.

Richardson says she is willing to accord the “Super Ten” title to anyone who buys her complete 10-beast oeuvre, minus all the expense of guns, permits and needful travel. Although a vegan and an animal lover, she admits to a certain ambivalence in her attitude to aspects of the hunting culture.

“My father was an avid hunter and collector of trophies. In his office, there was a deer, a boar, a bobcat, several ducks, a squirrel, and a snarling coyote,” recalls Richardson. “I grew up with these mounted forms around me, and it was normal. I remember being slightly terrified of the taxidermied animals and yet fascinated at the same time. They had a haunting aura. The animals, albeit dead, seemed alive. No blood, no mucus, and no internal organs: just preserved skins stretched over plastic forms. Their glass eyes shining, more perfect than the real thing.”

“As a vegan and an animal rights advocate, my fascination with taxidermy conflicts with my belief system,” Richardson continues. “The idea of using animals, dead animals, as souvenirs and trophies is appalling. That said, I am captivated: I want to reach out and touch their fur; feel the sharpness of their teeth and horns. I am hypnotized by their beauty.”

It was that stilled, perfect, animal beauty that she aims to capture in her paintings.

“I understand the desire, the yearning to be close to animals: swimming with dolphins, taking pictures with baby tigers, riding elephants,” adds Richardson. “I know because I feel it as well. I also feel that animals are individuals who deserve their autonomy, that our intervention in their lives often wreaks havoc. So I abstain and suppress my desires.”

‘’This push and pull of desire and repulsion is something I work into my pieces. The finished pieces are hauntingly beautiful: precise line work plays off dripping watercolor, shifting between flatness and form; the bright colors intercepted by geometric line work straddles the worlds of the representational and the abstract. I want my art to dance between ghostly and bold, to orbit between solidifying and melting away,” says Richardson.

“With Orion’s Lament I seek to commemorate each animal, while questioning the disparity I feel between being captivated and repulsed,” concludes Richardson. “I also intend to create a neutral space to acknowledge the beauty of animals and start a gentle conversation about conservation.”